This is War

Thoughts on Civil War, Gaza, The Purge, and fun stuff like that.

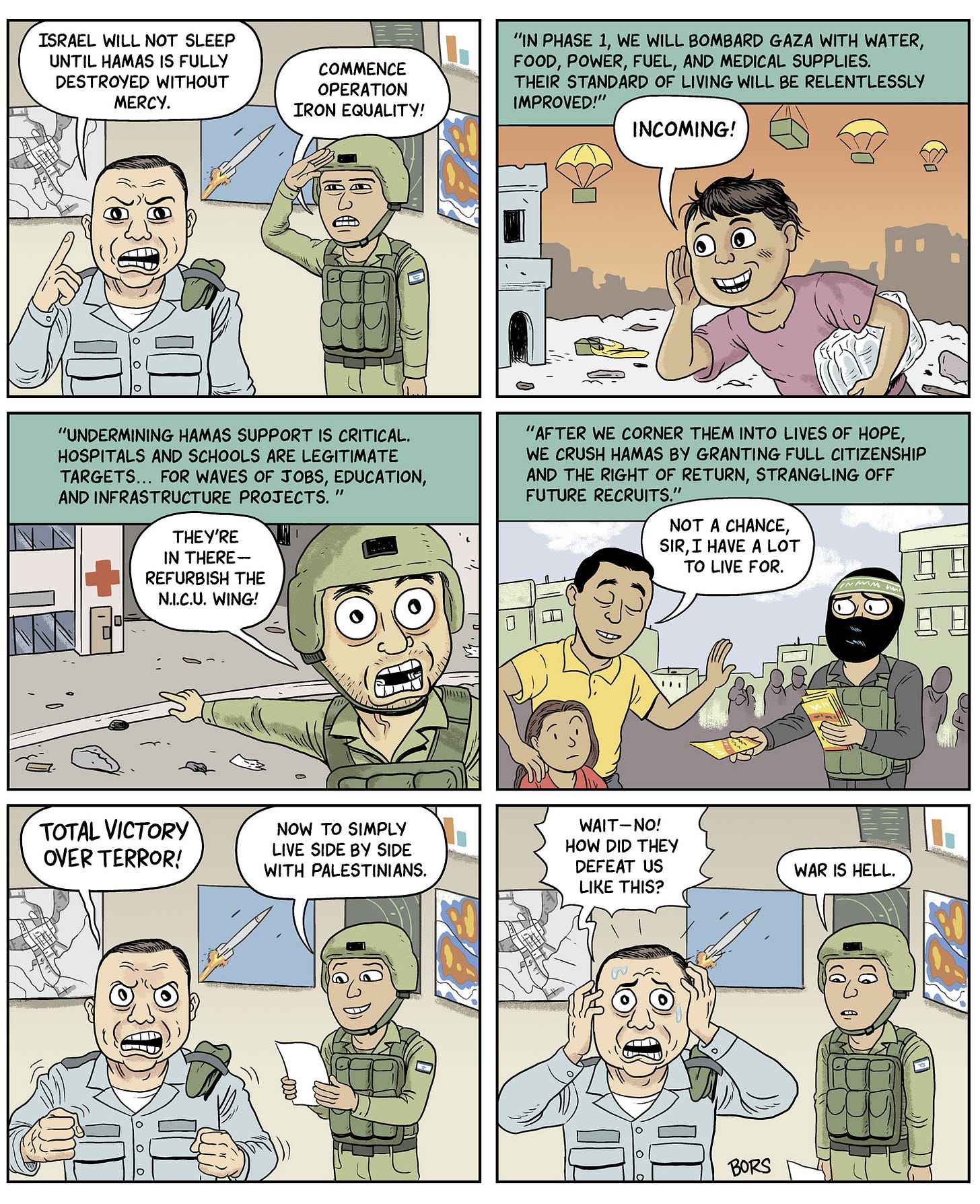

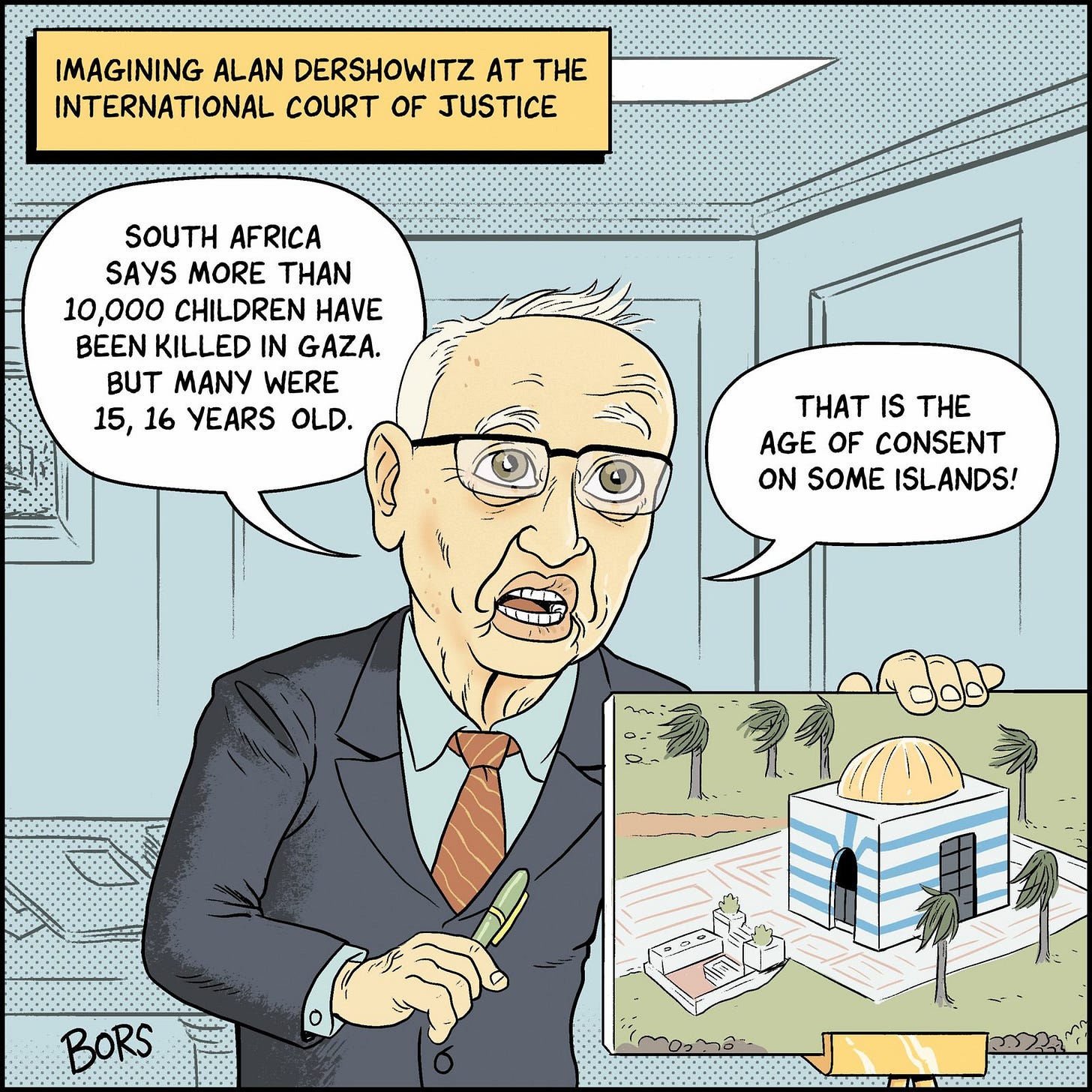

This newsletter features some ramblings on the movie Civil War and other media showing dystopian American conflicts such as The Purge series and the novel American War. Before I get into that, however, here are some recent cartoons from In These Times on the war in Gaza. In fact, the only two political cartoons I’ve created since 2021. Read the whole comics section for their most recent issue here.

The near-total implosion of Joe Biden as a viable candidate, along with the Supreme Court ruling on executive immunity, have people once again catastrophizing about a future of violent civil disorder under a rampaging president king. Not without merit! Trump has been saying the quiet parts even louder this go ‘round. The anxiety and dread around his possible reelection paint the worst-case scenarios in our minds: the US descending into an authoritarian state, round-ups of immigrants and political opponents, a president who refuses to leave office, collapse and civil war.

We were treated to the fantasy recently in theaters in the form of Alex Garland’s Civil War. The movies stars Kirsten Dunst as a photojournalist on a cross-country tour of the US ravaged by years of war, as various armed forces close in on a rogue administration that won’t leave office. Okay, sounds relevant.

The movie did well financially and critically, but in my corner of the social media world, filled with leftists and liberals, I saw a lot of derision at the premise and execution. Wasn’t this just a liberal parable about the need to get along? How could California and Texas form an alliance in another context outside of the rigid barriers of this precise moment in time? On top of that, the movie focuses on journalists. Yeah, “Democracy dies in darkness” but don’t give us a view from nowhere. Say who is good, who is bad, and what do their foundational charters promise. Which faction is the same type of socialist as you and I? There was palpable disdain from more politically active posters in my feeds for the movie not getting into the weeds on the four geo-political factions locked in open warfare.

The movie doesn’t offer answers, leaving the details and ideologies behind the conflict mostly off the table. Information is relegated to small off-hand comments that allude to mountains of news, history, and viewpoints the audience isn’t privy to. But watch it to the end and tell me it’s delivering a simple message merely meant to flatter journalism or liberals who imagine themselves as part of The Resistance. There was none of that in the movie I watched, which I largely attribute to viewing its content and thinking about it.

A leftist commentator I follow on Facebook posted that he quite liked the movie on a couple fronts and didn’t understand the dismissals. A comment responding to him captured the mood I’d been seeing since the movie’s release. “Really? I know absolutely know nothing about it other than the memes,” he wrote. “Just figured it was a right wing wet dream movie but, again, memes are the only context I have.”

Memes are the only context I have.

If we’re headed to war any time soon the left will have a pitiable army.

The more substantive criticisms, from people who have a little more than memes rattling around in their heads, seems to be a desire to put fascism on blast. Name the thing. Describe plausible political factions. Give answers! Assign blame! Deliver speeches! No weak liberalism with the underlying message to get out and vote for the underwhelming guy so the really bad guy doesn’t win.

The movie avoided any specific correlations with Trump and the election—wisely, I’d add. The result isn’t a glib anti-Trump movie, but a more straightforward anti-war film, in the best sense of that term. Meaning it depicts violence for what it is: something that dehumanizes and degrades everyone involved.

It also functions as a film, by which I mean its highest order is not plot and making points, but rather to create memorable images and sequences that prompt work on your end to digest and impart meaning to. Its focus on journalism is really a focus on images—Dunst’s character captures them over and over as a photographer. Garland, whether you like him or not, is clearly a filmmaker who puts a great deal of thought and intent into what you see on the screen. How you feel witnessing scenes of guerrilla war and checkpoints and executions set in your country is, to my mind, a better way to digest a movie than wanting the filmmaker to tell you his own ideas more directly.

Still chewing on the movie a week after viewing, I turned to my bookshelf to see the spine of American War by Omar El Akkad, a novel published in 2017 that I had purchased over the pandemic but not yet read. Would this slake my thirst for visions of societal breakdown as brother turns against brother? I drank it down.

The novel begins in 2074 with the prohibition of oil, which is pushed through after the president is assassinated for supporting the bill, which then leads a group of Southern states to secede and form the Free Southern State, though Texas is quickly invaded and occupied by an opportunistic Mexico and South Carolina is quarantined off into a dead zone after being attacked with a biological agent. The Capitol of the United States is now Columbus, Ohio.

If you like those details, this book’s got plenty more.

American War inundates with world building in the form of news articles and other ephemera stippled throughout the book. I eat up stuff like that and found myself wanting to go down the wikipedia hole of this entire conflict, then listen to a ten-part history podcast. That tendency, I began to realize, was distracting me from the story. As new details came in, they gave rise to more questions about the events, reactions, and plausibility of it all. More information begged for additional information to buttress the scaffolding the author had constructed. Maybe this isn’t exactly what we want in this vein of fiction.

The story starts relatively slow, following a young girl, Sarat, in an impoverished, climate-ravaged, and war-ridden Louisiana. She is soon relegated to an internal refugee camp due to the conflict. From there we follow her over the course of 20 years as events push her toward fighting for the Southern cause and making some critical contributions to world history through what could only be called acts of terrorism.

Despite the setup, Akkad isn’t very interested in parallels to the first and actual American Civil War or saying much beyond the obvious about oil. Easy statements are passed over in favor of staging a complex conflict in the US that looks a lot like how we wage war in the Middle East. By bringing the distant effects of the 2000s Global War on Terror stateside, Akkad shows what refugee camps, drone attacks, suicide bombing, detention and torture may produce in Americans if they found themselves unfortunate enough to be subjected to their own tactics on their own soil. The novel shows what a country in real decline, real failure, egged on by foreign intervention, really does to human beings. (The pandemic aspects also hit hard after 2020.)

The result is hair-raising. The protagonist is clearly on the losing side of history, a victim herself, but then, as she grows older and loses her innocence, she warps into something destructive and merciless. Yet we understand her fully.

This story isn’t about journalism and truth. I read it at the height of Israel’s war on Gaza as and it parallels were gut-wrenching. The novel explores the mass violence we will accept and the kind we will dismiss as savagery. It wasn’t hard to see resemblances of Hamas as the story sought to understand how radical and even nihilistic ideologies take hold in a battered population.

It’s easy to imagine that if a mere fraction of the brutality we have visited upon other countries came back on us, we would redraw the lines around impermissible savagery. If, say, another country used siege tactics to cut off electricity and food, Americans would start seeing very little distinction between civilian and soldier in the offending party by the 60 minute mark.

American War is not an uplifting book with a victory over fascism or a bad president unseated by a righteous democratic cause. In fact it’s told from the perspective of the unsympathetic cause and one of the bleaker endings I’ve ever read in my life, one that shows the costs of breaking people until they have nothing to offer the world but violence. I finished it on a plane and sat there quietly thinking about it for the next 30 minutes. There’s no glory in the violence. No position you can take that makes you right. No pat answers.

Now, if you want some more entertaining, visceral thrills in regards to murdering your fellow Americans, you can’t do better than the The Purge series. Launched with the titular movie in 2013, the series envisions an annual night of lawless violence where murder is legal for 12 hours. Over five films and a tv show, we jump forward and backward in time to show an America controlled by a fascist party using the Purge to eliminate undesirables while uniting supporters in a patriotic blood ritual.

In the second film, The Purge: Anarchy (2014), you get two things: 1) Some of the most explicit depictions of how the wealthy are sickos who want the poor killed off and 2) The best Punisher story ever put to film. The latter is courtesy of actor Frank Grillo, who looks very much like a grizzled Frank Castle and whose characters sets out on a mission of vengeance on Purge night only to be confronted with the fact that he still has a heart.

Purge: Election Year (2016) depicts the reigning political party, the New Founding Fathers, attempting to assassinate a Senator seeking to end the Purge legislatively while a violent revolution led by people of color sets to massacre the rich white Christian nationalists who kill the poor for kicks. If this ain’t what people are asking for then I don’t know what is!

Yet, when I mention the series to friends I’m often met with befuddlement. Never seen ‘em! Are those any good? Heard they were fascist! They’re political?

The Purge series is maybe the most overtly political films of the 2010s, ones that explain the rise of fascism, display its consequences starkly, and do not muddle their message or politics. It depicts and celebrates the violent on-screen slaughter of a fascist elite! Yet it also somehow ducked the 2010s culture wars, where everything was evaluated for its woke/anti-woke properties and dropped into “good” and “bad” buckets to argue about online with strangers.

The Purge series is successful (there’s a sixth film is in the works) but they don’t seem to be much on the radar of the left writ large or those at the forefront of discussing pop culture—i.e. the writers, people in entertainment, critics such as they still exist, the too-online posters, and all who desperately want a more political Civil War movie to exist.

My running theory is that popular film in the 2010s largely diverged into Marvel blockbuster fare with all-ages messaging and elevated A24 genre films that embodied our era’s desire for vibes and sophistication, that leaned off clear messaging. ( I like movies from both.) The Purge isn’t any of these things. Its trashy, decidedly un-elevated tone, and early 2000’s nu-metal aesthetics in the masks of Purgers seems to signal to the people who would most agree with the film’s message: this one’s not for you. And maybe it isn’t. Agreeing with a movie’s politics and enjoying watching it are two separate things.

Squid Games, another bleak and violent series that isn’t particularly subtle, became one of the biggest streaming hits of the decade. So there’s a taste for this kind of thing, I just don’t see The Purge referenced to the degree you’d expect—Election Year came out the year Trump won and presaged the coming era better than any piece of media I’ve seen.

Back to Civil War, the movie, and the desire to have politics—your politics—reflected in your apocalyptic fiction. I’m a fan of hard-hitting satire and don’t conflate subtly with seriousness (just have a look at my comics!) but I do appreciate Civil War leaving space for you to fill answers as well as American War’s detailed world-building that doesn’t walk over the more interesting, complicated story it is telling. I’ve come to think the more a story tries to directly appeal to those who agree, for the very purpose of agreeing together, the more likely it is that you’re reading a bad story.

If you accuse The Purge series of being too on-the-nose, I can’t protest. So maybe Civil War then is too subtle and allows for people to say it is not about what it is about. Maybe.

One of the film’s most notable scenes features a soldier, played by Jesse Plemmons, covering up a mass grave of civilians and killing foreigners on sight. I think I get what the filmmaker was trying to say there! The tendency is to reduce this to something along the lines of, “Alex Garland believes we should all get along with one another” and, yes, he is saying that to an extent and, frankly, it would be nice.

In an interview with Pod Save America, Garland was pretty up front about how he thinks: “If the left wants to combat right-wing extremism, it needs to be in the business of winning elections.”

Well, there you go. Garland is not a radical leftist who made a movie with a thorough critique of the Democrats failure or one who wants violent confrontation with the state or the paramilitary right and prioritizes winning elections over losing them. If you thought a mainstream Hollywood filmmaker was going to believe any differently, you have only played yourself. In the worst framing, he is status quo-mongering. But if you can pull yourself away from the tendency to form arguments around things in advance of seeing them, or the worry (compulsive demand?) that every viewpoint of a creator has to personally align with yours lest they be slotted into some mental grouping of people who irritate you, you can allow yourself to enjoy things a bit more.

Last week, with Biden catastrophically faltering before the world, everyone seemed to put down their posturing and, for a brief moment, acknowledge that they too, when it comes down to it, prioritize winning elections over losing them. Accepting that doesn’t change any fundamental critique of the overarching system we find ourselves in. A party that says fascism is on the ballot and that this could be our last free election has to act like it and campaign to win… with a candidate capable of winning.

In our world, we make hard, depressing choices with the best option in front of us in the moment with the hope that these contribute to, at bare minimum, a managed decline instead of a full collapse into fascism. The decisions that led up to this point don’t leave any sure-fire way to prevent Trump from winning. In every route, incredible risk.

I’m drawn to these types of stories because I enjoy gaming out political conflict and ruminating on disaster. Civil war dystopia is where we go to safely channel our fear that our government and our neighbors may soon kill us, but also to indulge in the fantasy that it would be fun and heroic to maybe kill them first. Or, if memes are the only context you have, think kombucha girl: “Civil war sounds real ugly. Unless…”

No one wants things to collapse so they can have been “right” about the need to be alarmed. Well, many seem to but they’d regret it instantly. Very few people will care by that point and, as mentioned earlier, the most memed-brained phone addicts angrily reacting to stimuli won’t be making it very far in block-by-block warfare.

What all these stories I’ve mentioned have in common is that, by their end, whether a more just society is restored or small battles are won, millions of lives have been lost and ruined forever. The satisfaction of seeing tyrants machine gunned is tempered by the realization that the point at which a real victory was achievable was long before these stories take place. They are glimpses into total political failure.

We’ll find out soon which track we’re on.

My new graphic novel, JUSTICE WARRIORS: VOTE HARDER, will be released September 10 and follows mutant cops Swamp and Schitt on undercover missions to subvert and protect Bubble City’s first election. Many of the ideas in this post—civil strife and state repression—will be on full display.

This second installment of Justice Warriors was made in the mold of a paranoid political thriller by way of Robocop. Call your local comic shop or bookstore to pre-order or order online through one of these outlets!

This post’s title takes its name from the song “This is War” by Ben Kweller. Normally a much more mellow performer, this track is his most hard-charging track and I often put it on when I need a jolt.

I can't be your friend

'Cause I got to knock you out

So I can win

Thanks, insightful observations are always welcome!

This was good writing and a great set of observations. Keep up the good work, Matt!